|

Cost reduction programs are in fashion once again. But slimming down costs does not necessarily lead to fatter profits

By Mark Connelly

Paying the price of cutting costs

Keeping up with the competition is no easy task in any industry and pulp and paper is no exception. One major paper producer claims that it takes $225 million of cost cuts every year just to stay competitive and involved in the game. At over $600,000 per day, this may sound like a lot of money, but other producers suggest equally significant cuts are required, depending on the size of the group in question. Indeed, most producers believe that ongoing cost cuts are essential and that greater levels of cost reductions form the key to better profitability. From an outsider's point of view, the equation looks somewhat different. Cost reduction is a critical operating imperative for paper producers, but its impact on earnings is usually minor and the implications for capital returns have tended to be negative. In highly fragmented commodity businesses, no amount of cost reduction is likely to result in sustainable bottom line improvement unless it is driven by proprietary technology or some other fundamental change. This would allow one, or a few, producers to compete on a basis which others cannot replicate or respond to competitively. In practical terms, this means that the more costs come down, the more prices should drop, leaving profitability more or less unaffected.

For most commodity paper grades, the relationship between cost reduction and higher profitability is tenuous at best. A glance at a handful of annual reports from the last decade will reveal that despite successful cost reduction programs, a drop in market prices has often left producers worse off than when they started. So are producers "chasing rainbows" in their cost reduction efforts? Not exactly. Without continuous emphasis on cost, commodity producers rapidly lose ground competitively. But if cost reduction is not improving the bottom line, producers need to take one of the following steps - aggressively reposition to reduce the commodity status of their products, or acknowledge their commodity nature and build a strategy that can shift the balance of power toward producers (or at least back toward the middle). Over time, the more commodity oriented a business becomes, the less likely a producer is to see cost reduction helping the bottom line. On the other hand, if cost cuts coincide with a commodity cycle upswing, they may just have some positive impact, for a while at least.

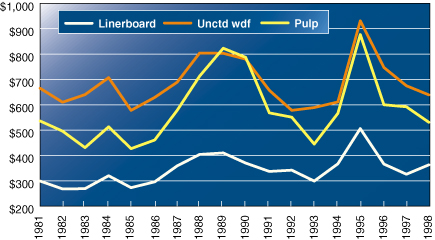

Figure 1 - NBSK Pulp Costs v Prices

The cost of cutting

For most commodity businesses, aggressive cost reduction is a cost of doing business. It is not a means to achieving meaningful competitive advantage, nor is it a particularly good way to boost earnings. At worst, it can pose a serious threat to capital returns. That cost reduction and lower prices should coincide time after time in a highly fragmented commodity business is more of a truism than bad luck. Managers at some companies have accepted that premise and are beginning to look elsewhere to create sustainable earnings power and shareholder value. This does not mean to say that cost reduction programs are not important, they are in fact critical. Commodity producers who are not constantly seeking ways to cut costs quickly end up as the high cost producer. But cost curves have become flatter in the past few years, evening out competitive positions and lowering costs for most companies. That is good news because it helps to keep the industry competitive, not because it results in higher profits. To some extent, lower costs and prices are a way of life in commodity businesses. With largely undifferentiated products, it is hard to see why customers should not come to expect suppliers to keep prices moving down. But when the supplier base is highly fragmented, customers very clearly have the upper hand in terms of pricing leverage. Every time the market becomes slack (which happens more often in fragmented markets), customers tend to get their way. In less fragmented commodity businesses, downward price pressure still exists, but the balance of power between producers and customers is more evenly spread. Cost reduction programs in less fragmented grades have a somewhat better record. For example, recycled paperboard producers have historically seen sustainable profit improvement from cost reduction efforts, and the same has been true in commercial tissue, albeit to a slightly lesser extent. Commodity markets with greater concentration tend to offer producers fewer rational operating strategies (but perhaps paradoxically, a greater opportunity to differentiate). As a result, those markets behave in what is perceived to be a more disciplined manner, whether or not there is in fact any discipline at work on the part of the participants.

| Table 1 |

| |

- 1995

|

- 1988-90

|

| |

Peak EPS |

P/E |

Peak EPS |

P/E |

| Bowater |

$7.36 |

5.4 |

$4.4 |

6.5 |

| Champion International |

$7.74 |

5.7 |

$4.94 |

7.1 |

| International Paper |

$4.68 |

8.4 |

$3.87 |

6.8 |

| Mead |

$3.13 |

8.8 |

$2.04 |

10.6 |

| Willamette Industries |

$4.68 |

6.2 |

$2.00 |

6.2 |

| Weyerhaeuser |

$4.83 |

9.8 |

$2.86 |

10.0 |

Balancing act

In the end though, even the success or failure of cost reduction appears to be contingent upon managing the supply/demand balance. The more fragmented the grade, the more apparent the pressure to reduce costs, which tends to detract from focusing on the bigger problem. Producers whose profits are constantly under pressure tend to behave as if their ability to affect the top line is limited and they choose to focus on the cost side instead. For smaller producers, that is a rational, if not a very promising, strategy. In contrast, large producers need to keep a consistent focus on strengthening their influence on the top line if they hope to achieve acceptable levels of profitability across cycles. But historically, many companies have not maintained that sort of focus.

Market segmentation can help producers hold on to cost reduction gains, but the advantages depend on the extent of the market segmentation. For example, US coated paper producers operate in fairly segmented markets - producers of #1 grades do not compete much with #3 suppliers. But even in coated paper, there is continual erosion at the bottom of grade categories, with heavy substitution in the lighter basis weights as well as competition from newer grades, like supercalendered (SC) paper and products such as Bowater's new "coated newsprint".

A few containerboard producers have successfully carried out market segmentation. For example, white-top linerboard has been a very good market over time with better than average results, and cost reduction efforts in this area should tend to have more economic impact. Similarly, a few producers have found success by adopting local account strategies and avoiding national account competition.

What these examples suggest is that to avoid passing cost reduction gains on to customers, producers need to find a way to get some leverage back. In highly fragmented businesses, producers tend to have very little leverage compared to their customers over a cycle. Conversely, where producers have managed to carve out niches within otherwise commodity grades, results tend to be better than average, depending on the strength of their niche.

In most of the major commodity grades, cost curves are getting flatter, at least on a national basis. To some extent, a producer whose costs are out of line can benefit by bringing them back into line. But as cost curves flatten out, the potential gains to any one producer shrink and tend to be swamped by other factors. This suggests that the potential upside opportunities for any individual producer are shrinking and the ability of other producers (even smaller ones) to compete on an equal basis may actually be rising (assuming relatively equal access to markets). This is not good news for the medium to large-sized producers.

When viewed in a global context, cost curves change considerably as foreign exchange swings turn cost structures inside out. Nearly all grades are affected by foreign exchange rates to some extent, whether the grade in question actually participates in the import/export market or not. As large foreign exchange swings take place, immense pressure is brought to bear on the higher cost currency producers.

Currency-hobbled producers (especially those who do participate in international trade) tend to respond with action aimed at lowering their costs in the new foreign exchange environment. But since the national cost curve tends to be pretty flat, no producer is likely to create really significant bottom line value in that process. Instead, the whole industry spends increasingly scarce resources (capital and otherwise) merely to stay in the game.

The upshot of this, of course, is that producers become stronger competitively. Indeed, foreign exchange rate fluctuations have been one of the primary reasons that US based producers have remained so well positioned in terms of relative cost competitiveness over the past decade. But there has been a hidden cost to all the years of cost reduction and productivity efforts. While US producers can proudly cite their strong global cost competitiveness over time, producers' ability to earn an acceptable return on capital has declined more or less in step with the capital spending that made cost reduction possible.

American Average

USA Paper is an imaginary company which has average raw material input (fiber, energy and labor) and financing costs. Assuming that capital equipment costs are roughly equal across markets, USA Paper should have something approaching an average return on invested capital. But if there is a sudden swing in foreign exchange rates and dollar strength, USA Paper will lose ground competitively and see export orders decline. The company may even find that formerly higher cost foreign producers are shipping product into the USA. As a result, USA Paper is likely to opt for cost cutting measures. If the company is lucky, the dollar moves lower, removing some of the competitive pressures. In any case, USA Paper spends some money to reduce operating costs and becomes an even more efficient producer.

But clearly, not every cost reduction initiative can earn a satisfactory return on capital invested, so USA Paper has to choose carefully. With currency swings and other pressures the norm rather than the exception, the pressure to invest to stay in the game is repeated and substantial. Over time, capital investments that looked too expensive earlier can seem vital in the face of new competition. As a result, USA Paper's capital returns begin to deteriorate. Of course, the company's costs are probably not really average. It takes upward of 30 years to grow usable hardwood trees in the US Midwest, twice the time taken in Scandinavia. This compares to just six or seven years in southeast Asia or Brazil. In the long run, USA Paper has no natural competitive advantage in fiber costs. Energy is more of a mixed bag because of the USA's well-developed power infrastructure, but labor is often much cheaper elsewhere. Added to that, environmental costs are rising in all markets, but they tend to be lower in many markets outside of the USA. So USA Paper's overall natural cost position is in reality probably somewhat above average. In view of this, it is surprising to see that the US industry has remained so competitive for so long. But most of the lower cost regions are not as well developed, which means there is not much capacity in those markets yet and their cost position is not particularly relevant. For example, if the upstart company, Brazil Paper, is only making a few hundred thousand tons/yr, it does not matter all that much if it can make a product at 50% of USA Paper's cost. But if Brazil Paper is growing rapidly and becomes a big player, its influence on market pricing begins to grow.

To some extent, USA Paper is probably building its competitive position at the expense of capital return prospects. As the US company pushes to counter the effect of natural cost disadvantages and swings in currencies, it invests in technology to reduce its most disadvantaged input costs, ie labor and fiber. Those capital investment costs improve machine productivity and allow the company to compete better, but they are expensive.

Over time, of course, developing markets will make progress and the Brazil Papers of the world are likely to grow. Eventually, Brazil Paper will be able to buy the very same (and sometimes better) technology that USA Paper has invested in. As those investments continue, all the relative cost improvement gains to USA Paper in labor and fiber gradually diminish. Arguably, they were only temporary anyway. But the capital USA Paper spent was far more permanent and may help hold back investment returns for decades.

Going forward, there are several areas where USA Paper could make improvements:

- invest in areas where natural cost advantages exist, or partner with someone with access to those advantages

- invest in strategies to segment and differentiate products

- carefully limit new spending on existing capacity to areas where long term benefits are most likely

- if the long term competitive advantages are not in the home market, then the bulk of new investment should probably also avoid the home market, or be geared toward shifting the competitive landscape away from basic commodity inputs.

Stick or twist

Companies should not confuse cost reduction, or "profit improvement" schemes, with restructuring programs. Restructuring changes the nature of the business or its strategic direction. Cost reductions just keep a producer competitive in a mostly status quo sort of way. There are really only two logical ways to escape the treadmill of cost/price reduction - by confronting the lack of commodity pricing power, or shifting the products away from commodity status. In a sense, it's a simple "fight or flight" argument.

If a company's products are smack in the middle of the pack, acknowledging a commodity position may make the most sense. In that case, the producer needs to build cost reduction into the culture of the organization, not the strategy. The distinction is critical because cost reduction is mostly a source of sustenance, not a source of growth, for commodity players.

Turning to strategy, the producer's goal must be to influence the balance of power between producer and customer. Service and quality can probably help, but mainly at the margin. For larger producers, the play may be as simple as getting bigger or stronger. But for small to medium-sized players, the situation is tougher. Getting stronger may mean selling, or aligning, or finding some other way to tap into someone else's strength. Many small to medium-sized producers think that by reducing costs they can let someone else consolidate and ride the coat-tails. This may work, but progress is slow and smaller producers tend to lose ground in consolidation.

Fixing the problem is not something that one company can do alone and that is really the crux of the paper capacity challenge. The problem is industry-wide and the solutions have to be company solutions. Collusion is not the goal - the goal is an industry structure that promotes constructive rather than destructive behavior. Champion's restructuring strategy of 'focus on strengths, monetize the rest' is one of the best examples around. Smurfit-Stone and International Paper's (IP) plant closures are an equally compelling approach, but with greater short term impact. There is more involved than just closing and selling capacity though, and as each producer examines its own sources of leverage and weakness, company strategies will tend to come into better focus.

Out of the rat race "Flight" does not mean giving up and getting out though. Instead it involves aggressively pushing a company's products away from the heart of commodity status. Westvaco is repositioning kraft tonnage away from containerboard and toward saturating kraft niche markets. IP and Champion's push toward branded uncoated freesheet could also be successful and the effort must be applauded. One concern is that together IP and Champion represent roughly 28% of the North American market. Shifting that much tonnage away from commodity status is not only an enormous undertaking, but might be merely a redefinition of what commodity status is. Smaller producers might be somewhat better positioned to succeed with this approach (if they can afford to shoulder the costs), but they will have to expect competition from the big players.

In general though, producers are already doing a very good job on the cost front. They should continue their efforts to drive costs lower, with increasing vigilance in assessing the return prospects of each new dollar invested. Occasionally, it may make sense to carry out a major cost reduction program in order to address big shifts in the business, changing management strategies, or new opportunities created by growth and acquisition. None of this is new and very little of it will create sustainable advantage. But it is a cost of staying competitive and it can lead to some shifts in relative market competitiveness for innovative producers.

The best step that producers could take is to think differently about cost reduction, stop hoping to gain much from it, and in turn, promising those gains to investors. That simple shift in mindset should make it easier to see that producers need to look elsewhere to generate gains for shareholders. Cost reduction should be approached more as a middle management operating imperative rather than as a strategic and competitive priority.

Mark Connelly is an industry analyst covering forest products companies at JP Morgan in New York. This is an extract from the report "Chasing Rainbows: The Empty Promise of Cost Reduction"

|